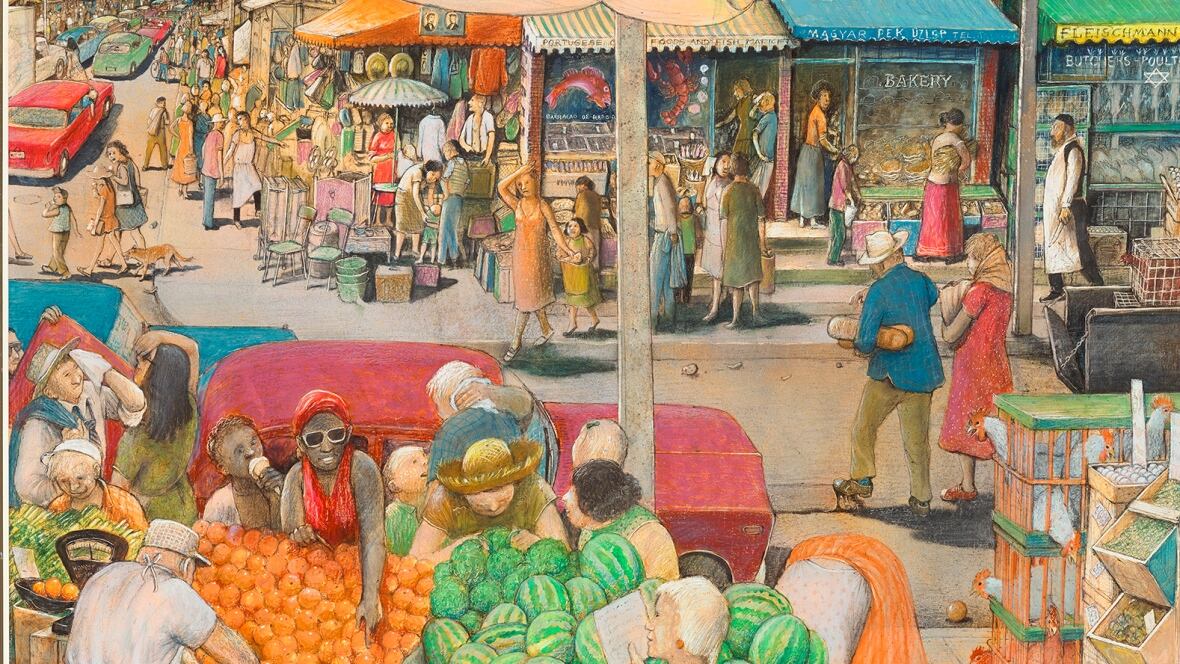

William Kurelek (Vasyl Kurylyk) art brutally showcased the harsh realities of farm life during the Great Depression. It also depicted the artist’s own profound emotional struggles. By the time of his untimely death, he was one of Canada’s most successful artists. To this day, Kurelek’s paintings remain highly sought-after by collectors because they offer an unconventional, and at times controversial, reflection of 20th-century anxiety. More than anyone else, William skillfully blended nostalgia and apocalypse in his work, creating pieces that simultaneously offer visions of both heaven and hell, according to edmonton1.one.

Childhood and Youth

William was born on March 3, 1927, on a grain farm north of Willingdon, Alberta, to Mary and Dmytro Kurelek. His maternal grandparents had arrived in the region east of Edmonton at the turn of the century, part of the first wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. These two farming families, originally from Western Ukraine, soon transformed the rugged Canadian prairies into a successful agricultural area and created a vital market for industrial development. Dmytro arrived in Canada in 1923 and married Mary in 1925. Two years later, their son William was born. In 1934, the Kurelek moved to Manitoba, settling on a farm near Stonewall. The move was likely prompted by the plummeting grain prices that accompanied the Great Depression, as well as a fire that destroyed their home in the early 1930s. When wheat farming in Manitoba yielded a meagre income, Dmytro turned to dairy farming.

William, the eldest child, spoke little English and was a cultural outsider in a community largely dominated by an Anglo-Protestant heritage. The move to Manitoba coincided with the start of William’s formal education, attending Victoria Public School during this period. Being a shy and insecure child, school wasn’t easy for him. He would later vividly portray his problems and anxieties on canvas. As a teenager, William was anxious and very withdrawn, earning him a reputation within the family as an awkward dreamer. The emotional turmoil caused by strained relationships with his parents, especially his father, shaped his path into adulthood. Dmytro relentlessly demanded practical solutions and physical endurance from his children, particularly his eldest son. While William’s brother John excelled at meeting his father’s expectations, William himself struggled to embrace the values his father cherished.

From his school years, William was drawn to drawing. In first grade, he decorated his bedroom walls with drawings of priests, snakes, and tigers, images he’d picked up from comics and Westerns. His parents were completely baffled by his drawings, but his classmates, on the other hand, praised and encouraged him.

In 1934, William and his brother John were sent to Winnipeg to attend Newton High School. For the first two years, the boys lived in boarding houses.

William attended Ukrainian culture classes at St. Mary the Protectress Church, a majestic Ukrainian cathedral located directly across from his home. The classes were taught by Father Peter, who not only sparked the young man’s interest in Ukrainian history but also became the first adult to truly appreciate his talent.

In 1946, Kurelek enrolled at the University of Manitoba, studying Latin, English, and history. He also took psychology and art history courses concurrently. It was during this period that William began to experience mental health issues that would define his adult life. He suffered from physical exhaustion, insomnia, social anxiety, depression, and very low self-esteem. Despite this, he did not seek medical help.

After graduating, he worked construction in Port Arthur and then at a logging camp in Northern Ontario, which he later depicted in his works “Lumber Camp Sauna” (1961) and “Lumberjack’s Breakfast” (1973). While this experience boosted William’s self-confidence, his emotional and mental struggles continued.

Global Travels and Battling Illness

In 1950, William decided to study under David Siqueiros in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. To fund the trip, he spent the summer and fall working as a labourer in Edmonton, living with his uncle before renting his own place. During this time, he painted his first masterpiece, “Romantic,” a Joycean self-portrait he later retitled “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” In the fall, Kurelek hitchhiked to Mexico. Along the way, in the Arizona desert, he experienced his first mystical encounter: in a dream, he saw a figure in white who told him to get up and tend to the sheep, otherwise he would freeze to death. William startled awake and ran after the sheep, only to see them vanish into the fog, and the figure disappeared. Kurelek later described this dream in his autobiography, “Someone With Me,” and used it as inspiration for the cover of the first edition.

It’s worth noting that William’s time in Mexico was a wonderful coming-of-age experience. It expanded his artistic potential and connected him to social issues like poverty in developing countries, among others. The painting “A Poor Mexican Courtyard” is a clear testament to this.

In 1951, Kurelek returned to Canada but didn’t stay long. At that point, he was concerned about his health and wanted to get examined and receive help for his escalating depression. However, he considered Canadian medicine incompetent and solely focused on money. Soon, circumstances led him to contact Maudsley Psychiatric Hospital in London.

In 1952, William arrived in England, and by the end of June, he was hospitalized for psychiatric treatment. The medical staff recognized his artistic talent, and since recovery was believed to depend on creative self-expression, he was encouraged to continue painting. In August, William’s condition improved, and he was discharged from the hospital. After that, he left England and embarked on a three-week tour of major art collections in Belgium, France, and Austria. Upon returning to London, Kurelek found work with the Transport Commission, which was involved in post-war reconstruction. In 1953, the artist’s mental state worsened, and he was hospitalized again. While undergoing treatment, he continued to pursue art. In 1954, William took a large quantity of sleeping pills in an attempt to commit suicide. After this, doctors prescribed electroconvulsive therapy, and his health improved again. During this time, the artist created several beautiful paintings depicting stamps, coins, and fabric fragments. Some of these, including “The Airman’s Prayer,” were featured in Royal Academy aviation exhibitions.

Career Development and Rising Popularity

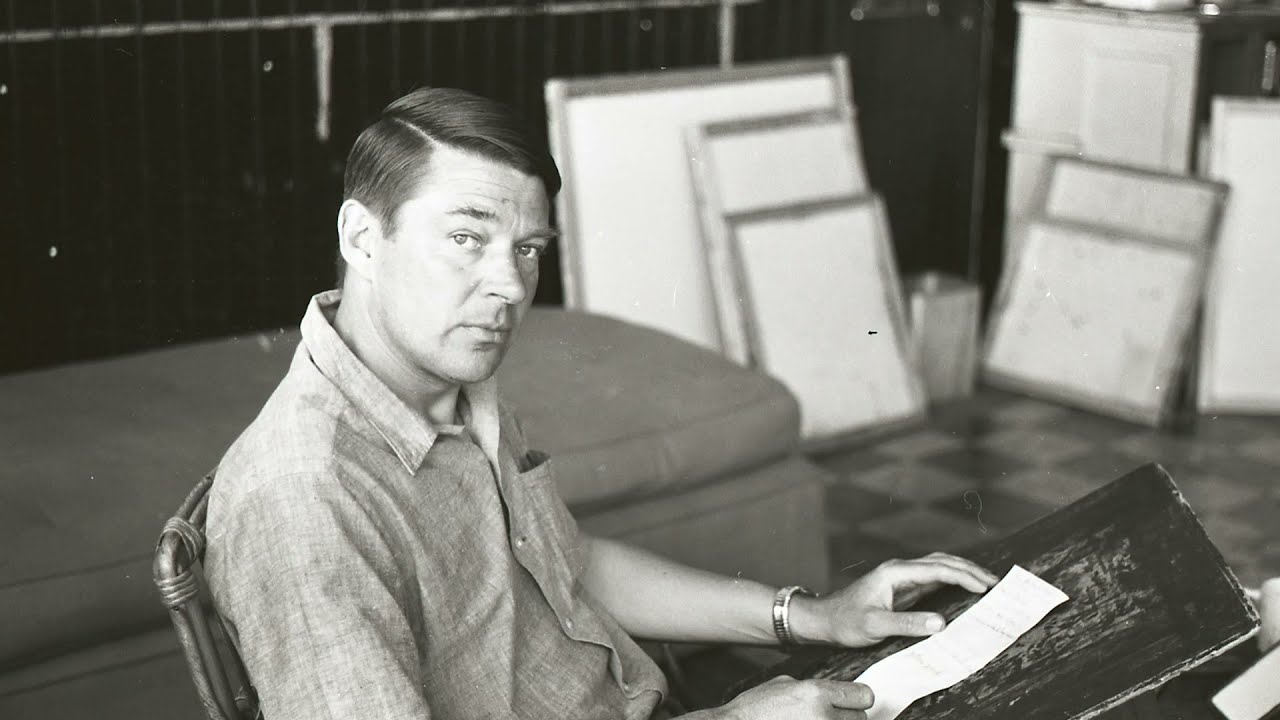

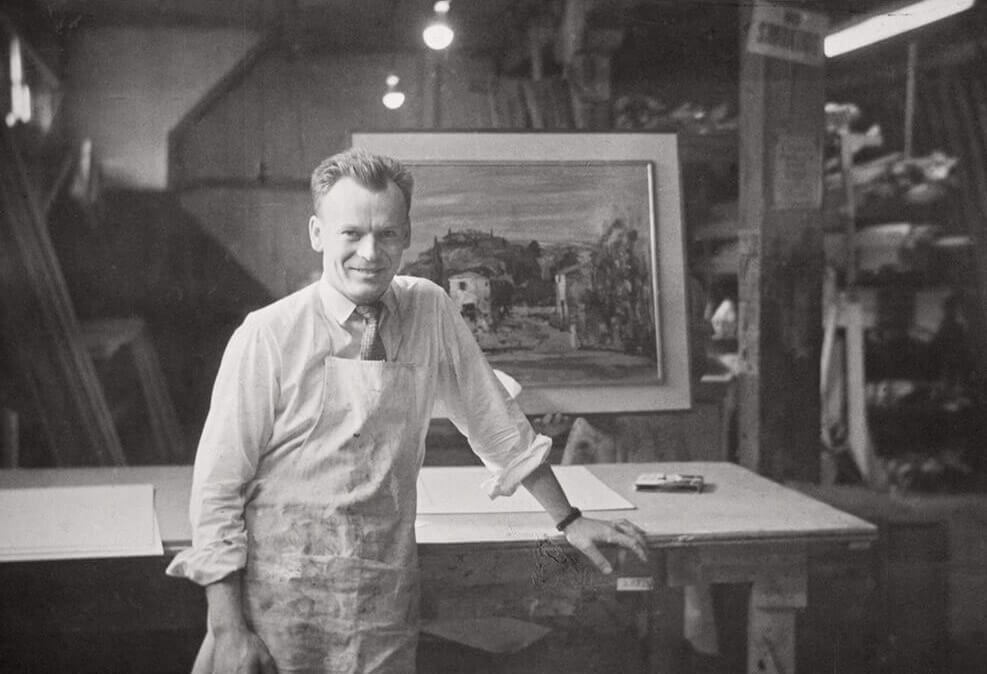

After therapy, the artist returned to London. In late 1956, he started working for F.A. Pollak Ltd., a company that manufactured and restored picture frames. He eventually became a master finisher, taking courses in frame making, carpentry, and book design at the Hammersmith School of Building and Arts and Crafts.

In 1959, Kurelek returned to Canada, living for a time with his parents on their farm in Vinemount. In the fall, he met Av Isaacs, who would kickstart his career as an artist and provide him with steady work. Isaacs owned one of Toronto’s first post-war contemporary art galleries. Deeply impressed, Isaacs offered William work in the gallery’s workshop and organized an exhibition for him in 1960. It’s important to note that Kurelek’s first professional exhibition broke previous attendance records. It showcased works created in England, and William’s unique paintings were positively received by the public. The work “Farm Boy’s Dreams” introduced viewers to another popular aspect of the artist’s work – nostalgic memories of his youth spent in Alberta, Quebec, and Manitoba. Soon, Kurelek became so popular that his works were exhibited in other major shows across the country. Over the next decade, the artist illustrated several successful books, including W.O. Mitchell’s “Who Has Seen the Wind,” “Fox Mykyta,” and others.

Later Years

Achieving fame, William gained confidence and found his true self. In the early 1960s, he met Catherine Doherty, the founder of Madonna House, an apostolic Roman Catholic training centre near Toronto. He then painted “The Hope of the World,” partly inspired by Doherty’s efforts.

By the mid-1960s, Kurelek love for the Canadian prairies resurfaced. In the following years, he travelled throughout Western Canada and the Pacific Coast, sketching. Concurrently, William organized exhibitions showcasing series such as “Experiments in Didactic Art,” “Glory to Man in the Highest,” and “The Burning Barn.” These reflected the artist’s personal pleas against the political consequences of speculative morality. William blamed the Cold War and environmental degradation on the immorality of Soviet and scientific humanism.

In 1970, William visited Ukraine for the first time, seeing his ancestral village. This trip inspired him to create the documentary work “The Ukrainian Pioneer.” With the advent of multiculturalism, Kurelek’s interests expanded to include other linguistic, ethnic, and religious groups in Canada. Before his death, he completed a series of works about the Inuit, as well as Canadians of European, Polish, and French descent. In 1977, after returning from his second trip to Ukraine, William was hospitalized. On November 3, he died of cancer. Throughout his life, the artist created over 2,000 unparalleled paintings and illustrations.