Kent Monkman, a Cree artist from the Fisher River Nation in northern Manitoba, has garnered significant acclaim for his work across Canada, with his art highly respected in cities like Edmonton and Calgary. For a deeper dive into his life and creative journey, keep reading on edmonton1.one.

Early Life and Childhood

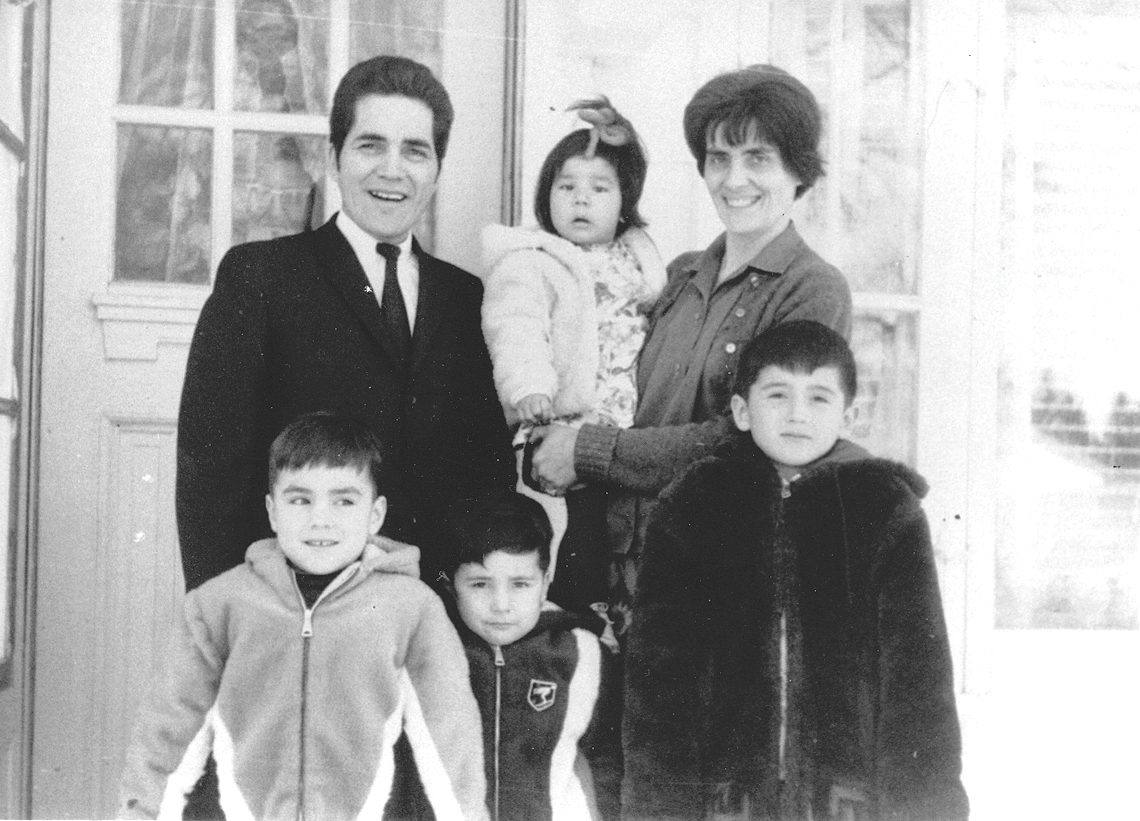

Born in 1965, Kent was the third of four children. His parents, Rilla and Evert, initially lived in St. Marys, Ontario, but after Kent’s birth, they moved back to northern Manitoba, settling in the Cree community of Shamattawa. Before marriage, Rilla was a teacher, while Evert worked as a commercial fisherman. After relocating to Winnipeg, Evert supported the family by juggling jobs as a social worker, taxi driver, and vacuum cleaner salesman.

Hoping to provide his children with a better life, Evert moved the family to the affluent River Heights neighbourhood, home to the city’s middle and upper classes. This allowed Kent and his siblings to attend one of Winnipeg’s top public schools. However, many residents in the area reacted negatively to the Monkman family’s arrival, openly expressing their disapproval. It’s worth noting that the family’s struggles with Canadian racism, colonization, Christianization, and language loss deeply influenced Kent’s artistic practice.

Monkman showed an early interest in art, and his parents always encouraged him. He’d fill pages with colourful pencil drawings, each telling a story. Soon, he was one of just two elementary school students selected for free Saturday classes at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. This access to high-calibre art education profoundly changed the young boy’s life.

Another Winnipeg institution that left a lasting impression on Kent was the museum. During a field trip, he was captivated by dioramas featuring mannequins dressed in traditional Indigenous attire. These scenes depicted Indigenous peoples pre-contact, seemingly frozen in time, hunting bison and setting up camps in idyllic prairie landscapes. From a young age, Kent felt a stark disconnect between these idealized representations and the ongoing, catastrophic consequences of colonization. Winnipeg itself was a city rife with racial and class tensions; a large part of its Indigenous population lived in the culturally diverse, economically struggling North End, rather than the predominantly white Anglo-Saxon River Heights where the Monkmans resided. In the museum, the young Kent recognized he looked different from his white classmates and keenly felt this contrast. He described his museum visits as both thrilling and traumatic.

Studying Art and Finding His Path

After graduating high school in 1983, Kent enrolled in the illustration program at Sheridan College of Applied Arts and Technology in Brampton, Ontario. He loved the curriculum, which included foundational courses in painting and drawing. During this time, he admired artists like Joane Cardinal-Schubert, Robert Houle, and Ivan Eyre. In 1986, Monkman earned his diploma and began working as a designer in Toronto for Native Earth Performing Arts, led by Cree artistic director and playwright Thomson Highway. Notably, this organization is Canada’s oldest professional Indigenous theatre company.

Kent’s responsibilities included creating sets and costumes for various productions. Indigenous theatre experienced rapid growth in the 1970s and became a significant part of mainstream Canadian theatre in the 1980s. Monkman’s talent in theatrical design and his interest in performance later had a strong influence on his artistic output.

Monkman also worked as an illustrator for a time, which exposed him to the city’s vibrant cultural scene. There were periods when the young man faced financial struggles due to low-paying work. Despite these challenges, Kent held independent exhibitions with other artists in his own studio, and in 1991, he participated in his first professional exhibition, “The Toronto Mask Show.”

Kent garnered public attention by illustrating Cherokee writer Thomas King’s children’s book, “A Coyote Columbus Story” (1992), written as a protest against the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s 1492 invasion of the Americas. The artist’s vivid, cartoon-like images, combined with King’s humorous and deeply insightful text, stirred political outrage. This work directly challenged the dominant colonialist narrative that glorified explorers and their “discoveries.”

Career Development

As Monkman’s artistic career evolved, political events strengthened Indigenous solidarity. Mass protests erupted in British Columbia, Yukon, and Ontario. In 1989, the Quebec government announced plans to begin the second phase of the James Bay hydroelectric project, sparking public outcry and leading to the suspension of work. The following year, Elijah Harper, a Cree Member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly, rejected the Meech Lake Accord, a proposed constitutional amendment that denied recognition of Indigenous peoples.

In the summer of 1990, a land dispute flared between the town of Oka and the Quebec provincial government. Mohawks defended a cemetery slated to be converted into a golf course. Monkman was inspired by the artists and activists involved in the protests and supported their cause.

In 1992, amidst widespread celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Western Hemisphere, two landmark exhibitions, including “Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives in Canadian Art,” boldly challenged colonialism. Beyond introducing Kent to the work of Bob Boyer and Jane Ash Poitras, they also exposed him to a range of Native American artists. Both exhibitions brought critical attention to contemporary Indigenous art, which, until the 1980s, had largely been excluded from many museums, including the National Gallery of Canada.

Continuing his studies at various institutions across Canada and the U.S., including the Banff Centre for the Arts, Monkman seized every opportunity to establish himself as an artist. He had been drawn to abstract expressionism since the late 1980s and was exploring this style even before he began creating works in that vein. The artist started experimenting with abstraction in 1990, contemplating the impact of Christianity and government policies on Indigenous communities.

In a major series of abstract paintings titled “The Prayer Language,” which includes works like “Oh For A Thousand Tongues” and “Shall We Gather at the River,” Monkman intertwined syllables taken from Cree hymns. In this series, the artist delved into themes of colonialism and reflected personal sexuality within the works.

New Directions in Painting

Around 2001, Kent continued his experiments with watercolour. Seeking clearer communication with his audience, he shifted from abstraction to figurative art. In several works, he depicted male figures in simplified but ambiguous landscapes and began reinterpreting Tom Thomson’s iconic paintings. The romanticized images of the Canadian landscape as an uninhabited wilderness became significant to him; he saw history as a mythology shaped by power and subjugation. In his piece “Superior,” the artist presented images of submissive cowboys and dominant Indigenous people. His goal was to use this dynamic as a means of exploring broader issues of Christianity and colonization. Soon, Kent decided to move away from using text and focused on landscapes, incorporating characters from mythology, such as hunters, pioneers, and missionaries.

Monkman continues to create unparalleled paintings with profound narratives, playing a vital role in shifting the cultural landscape. His work and critical insights are more necessary than ever in the process of restitution. Believing that art can be a powerful force for social change, and inspired by the resilience and resistance of Indigenous peoples, both historically and in the present, he focuses on transforming darkness and creating a transcendent experience.